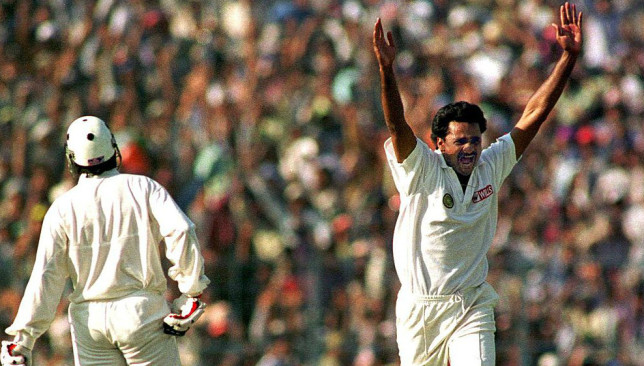

The date is March 13, 1996. The match is a World Cup semi-final. It is the first over, and Sri Lanka are batting. The ball is bowled short outside-off stump and Romesh Kaluwitharna’s mad swing is caught at third man. Three deliveries later, Sanath Jayasuriya is dismissed in exactly the same fashion.

Sri Lanka, one of the most feared sides in ODI cricket are 1-2. The most explosive pair in world cricket has been removed, Kolkata has turned into the City of Noise and India believe, nay know, they can win.

Unknown is the infamy that lies in wait and in the space of four balls, Javagal Srinath has posed one of the biggest “what if?” questions in the history of Indian cricket.

Srinath was 26 then, four years on from his international debut against Pakistan in Sharjah, where he bowled nine overs and claimed the wicket of Wasim Akram.

The Pakistani was undoubtedly his country’s best fast bowler – quick, with the ability to make the ball swing and seam at will, rousing crowds and energising team-mates.

It is a description that could also be used for Srinath.

Raw pace has no equal in this sport when it comes to capturing the imagination. Not only does it enthral fans, it is also a huge psychological boost for any side that has it stored in its armoury.

There is an aura that surrounds fast bowlers. Michael Holding’s came from his searing pace, Dennis Lillee’s his intimidation and Malcolm Marshall’s by preying on the fear of the opposing batsmen.

But Srinath was not of that ilk. The Karnataka man was one of the fastest bowlers India has ever produced, and in the immediate post-Kapil Dev period – when the Indian selectors played Russian roulette with a series of hopefuls – Srinath was Indian fast bowling’s candle in the wind.

Kapil’s 434 Test victims – that at that time made him the most successful bowler in the history of Test cricket – were hard to follow but Srinath plugged the gap and then some. Srinath remains the seventh-highest wicket taker in Indian Test history and third among fast bowlers. But his numbers were one thing; the effect of Srinath’s presence on his team-mates was another. Captain Sachin Tendulkar, ahead of the tour to the West Indies in 1997, ominously articulated that they would be in for a tough time if something were to happen to their pace spearhead.

He had tempted fate. Only a few days after the Indians landed, Srinath tore a rotator cuff in his shoulder and was sidelined. Demoralised, humiliation followed for the Indians in the Test and ODI series. Later in the year, with Srinath still absent, the Indians allowed Sri Lanka to post the highest score in the history of Test cricket – 952 for 6. An attack containing the likes of Rajesh Chauhan and Nilesh Kulkarni were firing blanks.

Five years later, it was another of Srinath’s young team-mates from the ‘90s who called upon the seamer that had defined so much of India’s cricket in that decade. Sourav Ganguly’s side were again in the West Indies and the captain had made fervent overtures to the old warhorse to help his side in their time of need. He was ready.

The home side kept defying the Indians’ pursuit of victory, but Srinath led the fightback. After ten years of Test cricket and 60 Tests behind him, Srinath bowled with all the enthusiasm of a debutant. He took three wickets during the chase (six in the match) and India won by 37 runs. It was the fourth and final overseas win of his 67-Test career.

It was a pretty exciting time to be an India fan during the 1990s if you were from Karnataka. Not only was there a young batsman by the name of Rahul Dravid, the bowling attack was led by a trio from that state: Srinath, Venkatesh Prasad and Anil Kumble. Between them, they collected 951 Test wickets.

Of those, Srinath contributed 236 wickets at 30.49, an economy of 2.85 and a strike rate of 64. From 32 home Tests, Srinath has 108 wickets at 26.61 at a strike rate of 55.8. Away from home, Srinath actually has more wickets (128), but an inferior average (33.76) and strike rate (70.8).

His wickets-per-game (wpg) ratio in his Test career stands at 3.52. In home games, this drops to 3.37 wpg, and in away games it reads 3.65 wpg. Remove those first 12 games, and it soars to 4.13 wpg.

On debut, Srinath scored 33 runs against Australia in Brisbane. For once he was out, and it was a contribution that was more than handy for a last man in.

Srinath hit a purple patch in the years 1994 and 1995 – this time with the bat. In nine innings, he accumulated 158 runs at 31.6 and an eye-catching strike rate of 61.71. He even managed two half-centuries.

For the corresponding time in limited-overs, his record was just as impressive. In the years ’94, ’95 and ’96, Srinath, in 35 innings, gathered 361 runs, a half-century and a strike rate of 93.76.

In 229 ODI career games, he collected 315 wickets at 28.08. Srinath wasn’t always the most stingy bowler (an economy of 4.44), but away from home, his average fell to 25.68 and his economy to 4.14, while his wpg climbed to 1.41. He also has 44 wickets in 34 World Cup games.

Today, the world is accustomed to Srinath in the role of an ICC match referee. This new commitment represents an intriguing new challenge for the former fast bowler. He had previously dabbled in cricket administration; his ex-on-field colleague Kumble became his team-mate off the pitch as well when the two revolutionised the Karnataka State Cricket Association from 2010-13.

Their time in office was marked by the spread of cricket across the state, development of top-of-the-line academies, the setting up of new infrastructure, the refurbishment of old ones. It’s all quite a change from the past, that mystical time when Srinath could often be seen hurtling in to bowl deliveries at ferocious, aggressive pace.

The sepia-tinted days of the 1990s may be over, but Srinath’s legend is not. He has a new occupation now, and performs his duty with focus and regularity, but it is yet interesting to view that sunny day in March 1996, when Srinath turned the world on its head in one over, in the larger context of his career. For some time he gave Indian fast bowling hope.