The time to dust off English football’s enduring debate is fast approaching.

Rumblings about a lack of winter break will steadily gain volume until they become deafening in the wake of this summer’s predictable round-of-16 exit at World Cup 2018.

But whether the critics have chosen the correct scapegoat is an issue of contention. Holistic failures in technique, education and policy also play prominent roles in the fact the Three Lions have won just six knockout-stage ties in major tournaments since lifting the Jules Rimet Trophy on home soil in 1966.

What cannot be denied is that when the rest of Europe’s big-five competitions are experiencing warm-weather training camps across the globe, the Premier League’s cast of mega stars are thrust into their busiest part of the calendar.

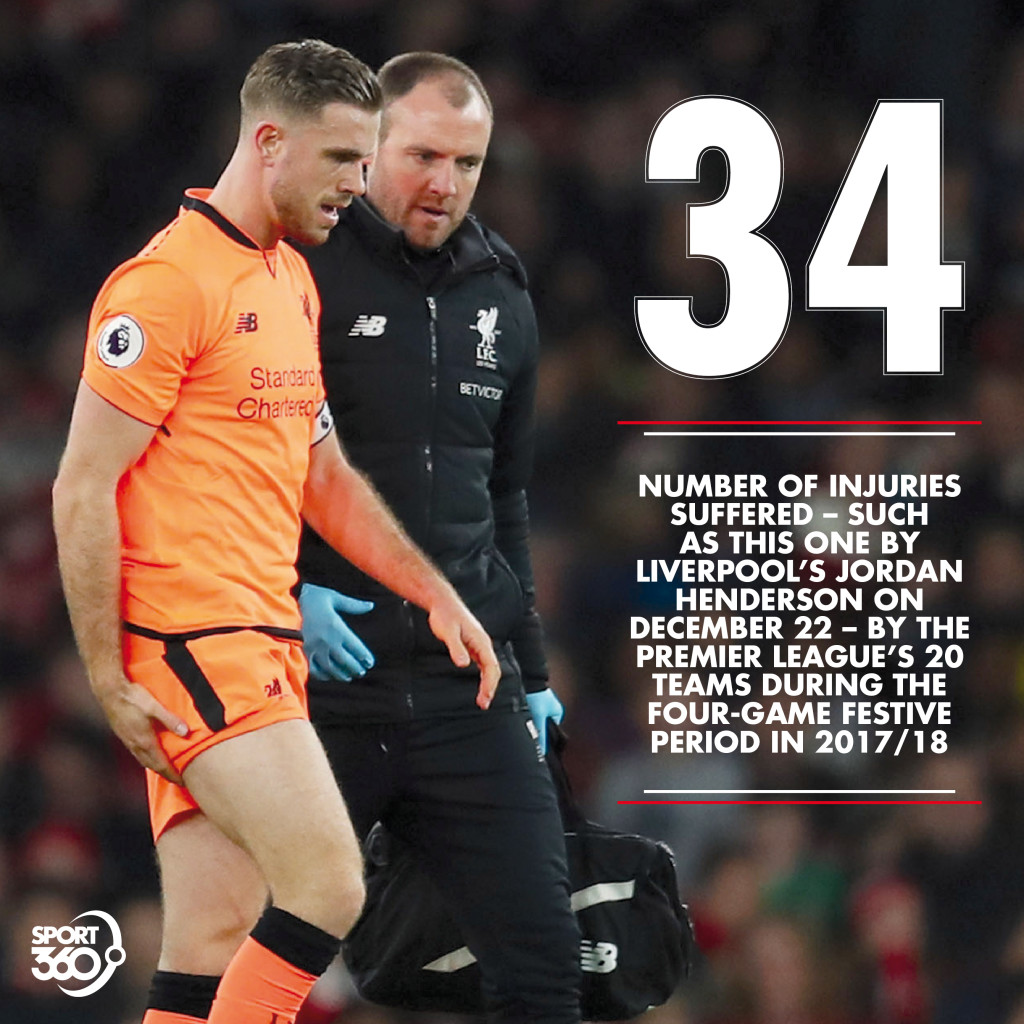

From late December to early January, fixtures are usually played every three days. With weather conditions biting and pitches often showing worrisome wear, injuries are an obvious side effect.

Intriguingly, this tradition could be melting away. Serious discussions were held by key stakeholders at the Premier League, FA and Football League recently to explore the possibility of introducing a two-week stoppage in mid-January.

Whether this is the panacea to the country’s footballing ails remains to be seen. Few judges are better placed than Pep Guardiola.

When discussing the effects of the winter break, the current Manchester City head coach made an unfavourable comparison to his time at Bayern Munich in the wake of February’s 4-0 thumping of Basel. The Swiss side had recently been out of action for seven weeks in the build-up to a one-sided round-of-16 opener in the UEFA Champions League.

“I had my experiences coaching in Germany and I have to say that in the winter break – maybe Raphael Wicky, the coach of Basel, knows it better – you lose your rhythm, you have a lack of rhythm,” Guardiola said.

This viewpoint comes from an issue of team performance. What does science say?

Tim Gabbett’s ‘The training-injury prevention paradox: should athletes be training smarter and harder?’ study from 2016 in the British Medical Journal argues there is a relationship between high training loads and injuries, although well-developed physical qualities protect against injury.

Surely, the extensive, hi-tech medical departments of the Premier League could devise ways to guard against such problems? But even then, complications exist.

Kane Read is a sports physiotherapist at Orthosports Medical Centre, Dubai. He has a firm belief increased athleticism in modern football makes the lack of a winter break a graver issue.

He tells Sport360°: “Players are in better condition, year-on-year, with the progress in sports medicine to be stronger, faster, fitter.

“The complications of this is that players create bigger, rotational, torque, acceleration and de-acceleration forces through their joints and it is these forces which cause most of the non-contact, soft-tissue injuries we see.

“So with Premier League players being fitter, stronger and able to tolerate more lactic acid in their bodies, they get closer to exhaustion and therefore are placing more load on non-contractile tissue which they are unable to strengthen as effectively.

“I think the lack of time between games in the winter negatively impacts performance. Readiness of players is hard to achieve then.

“The most common injuries you’re likely to see with this overload is soft tissue injuries, muscles, ligament tendons through non-contact incidents (sprains, strains, twists, tears).

“Statistics show that muscle injuries were up 45 per cent this winter (December 2017) compared to the rest of the previous months of this Premier League season.”

Including cup and league games for 2017/18, Spain stopped for 11 days from December 23-January 3 and Italy went on hiatus for 15 days from January 6-21. France added one more day of inaction from December 21-January 6, while Germany’s elite clubs sat out a revitalising 22 days from December 20-January 12.

In contrast, Premier League leaders Man City fulfilled 10 fixtures from December 10-January 9.

The coach of Arabian Gulf League champions Al Jazira, Henk ten Cate (left), has first-hand experience of both sides of this argument. As an assistant, he relaxed through the peak winter weeks at Barcelona and ramped up the workload at Chelsea.

It is an issue he has been unable to escape in the UAE.

“This [lack of winter break] affected us [Jazira] already in the whole month of December and now of course January,” the Dutchman says.

“Not even in Europe are that many games played, this is a reason why we have a couple of injuries.

“From today [January 16] until April 29 [end of UAE’s season], some of our players will play 30 games, whether we like it or not.”

The pernicious impact of this fixture congestion is proven by statistics. Research by www.physioroom.com for the 2016/17 Premier League shows players drained by the rigours of late December became more susceptible to injury. January’s tally of 143 reported problems is the second highest behind April’s 144.

For Kane, April’s peak is also tied into the strenuous winter demands.

He says: “As a physiotherapist, there are many things we can do to keep the player feeling right for a game knowing that the following week we can work, rehab and progress the injury over the next week before they play again, making week-on-week progress until a return to full fitness.

“With the winter break this is impossible, it will be management only. This means players come into the latter part of the season competing for the big trophies and fighting for their space in the national squad.

“By the time they have sufficient time to rehab and recover the acute injury they had in December, it is now a chronic injury in May.”

The empirical evidence is substantial about the need for a stoppage. Yet for ex-Chelsea, Barcelona and Iceland forward Eidur Gudjohnsen, its absence “makes English football” and a certain charm would be lost.

“It [the winter break] is a good thing,” he says at JA Centre of Excellence for a Football Escapes course. “I think when you come into that part of the season, it’s good to have a rest.

“But in saying that, I love watching Boxing Day football. It is what makes English football.

“If you take that away, I don’t know, I think you would lose a lot.”

English football, then, has a decision to make about whether its intrinsic philosophy or draining physicality matters most? The argument continues.