As the countdown to the2015 World Cup nears completion, it’s been fascinating to see the fierce debates raging over social media regarding the Pakistan-India match that is supposed to set the World Cup alight.

Beyond the rabid fandom of those who intrinsically believe that their team will win every future match regardless of the form or their most loathed rivals, a modicum of the respective fanbases are attempting to downplay their own team’s chances.

In one corner stands India, a team that just finished a two month long tour without a single win but remains reigning World Cup champions; in the other is Pakistan, home to 10 losses in their last 12 ODIs and a squad without its most potent threat. Each side seems more desperate than the other to secure victory, and it’s obvious whose fans have the right to be worried more.

Those that haven’t seen Pakistan over the past twelve or so months would be forgiven for thinking they remain a bowling powerhouse. Since the start of 2014 Pakistan’s average per wicket is just north of 40, easily the worst among the Test playing nations. In fact it’s over five runs per wicket worse off than next in line, Zimbabwe.

Furthermore, the West Indies are the only team other than Pakistan to have an economy rate higher than 5.50 during this time period. It all makes for poor reading for Pakistan fans and shows that their bowlers are not only unable to take enough wickets, they also struggle to stem the flow of runs.

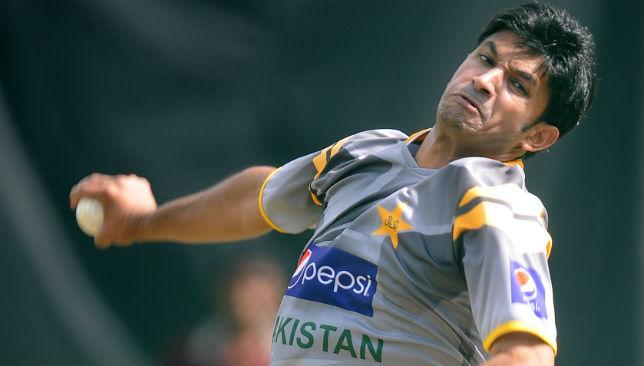

The problems with the bowling unit are twofold. They have a group of second/third-change seamers and no Saeed Ajmal to call upon for some magic and mystery.

Pakistan’s resort to a spin-led attack over the past five years or so did not come about as a specific strategy, but an attempt to maximize the only quality bowlers they had left. In the absence of their banned spinners, the onus has once again fallen on the quicks to shoulder the workload.

Junaid Khan’s injury has hindered those plans but has given the unheralded Rahat Ali a chance to impress with his left-arm seam.

Since the 2011 World Cup, each of Sohail Tanvir, Wahab Riaz, Bilawal Bhatti and Anwar Ali have played at least nine ODIs, none of which average south of 40. It is only Tanvir (with 5.25) that has an economy rate under 5.50.

Together with the decline of Umar Gul and similarly poor performances from those who have been given even fewer chances (Mohammad Talha, Ehsan Adil, Rahat Ali, M.Sami et al), Pakistan find themselves in a hole that they are struggling to find a way out of.

One of the only bowlers to come out of this period positively is Aizaz Cheema, but he too was found wanting at crucial stages.

At this juncture it is important to remember that Pakistan has never been the home to great pace attacks barring a short period at the turn of the century. From Fazal Mahmood (with the occasional help from Khan Mohammad) up until the fearsome duo of Wasim Akram and Waqar Younis in the mid-90s Pakistan never really had the equivalent depth of a McGrath-Gillespie-Lee or Steyn-Philander-Morkel attack.

Until the mid-90s Pakistan always had two or fewer world class pacers at any given time. By the time Waqar came through, Imran was on the decline. Similarly, by the time Shoaib Akhtar became the biggest draw in the box office the two Ws were at the end of their careers.

In ODIs Waqar averaged nearly 30 with the ball at almost 5-an-over with Shoaib present. Decent figures by mortal standards but not by those that Waqar set at his peak. And Wasim averaged 35 with the ball in the 10 Tests that he played with Shoaib Akhtar, despite having not lost any of the magic he was seemingly born with. And that, lest we forget, is the closest Pakistan have come to a truly world class three-pronged pace attack.

Since then Pakistan have continued to have at least two exciting fast bowlers come through every generation, but the great tragedy is that they never overlapped to make it a more substantial, varied attack.

At the turn of the century it was Shoaib, Sami and Zahid, in the mid 2000s Gul and Asif, and at the end of the decade Junaid and Aamer. The closest Pakistan came to deploying more than just the bare minimum was toward the end of 2009 and most of 2010 until the spot fixing fiasco.

Although even during this time Umar Gul could not compete at the levels that Mohammads Asif and Aamer were setting. But what would Pakistan give to return to that era, where the third fast bowler may not have been world class, but he at the very least could restrict runs at one end while damage was done at the other.

Having lost three generations in a short period of time Pakistan find themselves devoid of what they are still famous for – quality fast bowling.

As a result they are at a stage where bowlers who struggle to strike fear into domestic batters are to be thrust upon the world’s biggest stage as the country’s premier bowlers.

This illustrates the reason for the desperation with which Aamer is being courted back into Pakistani cricket circles and his return to the international stage will be more than a welcome one for the team and their legion of fans.

Pakistan will hope that the return of Aamer and Junaid might salvage a receding reputation, but until then Pakistan will have to rely on its batsmen to do their bidding. And that is a strategy that has rarely been worth relying on.