India’s big cities are formidable production centres for countless state and national level cricketers. For years on end, large metropolitan areas produced successful Ranji Trophy and Test players by the boatload.

Along with being places of great economic, political and historic significance, sprawling urban conurbations were almost akin to the old royal cities of Indian cricket – the places where the game’s legends grew up, learned their trade in or both.

Chennai, Mumbai, Delhi and Bangalore feature among them. It is safe to say, however, that Ikhar, Gujarat does not.

This is the place that Munaf Patel calls home. The journey from this village of sub-10,000 people to the Indian cricket team came via a ceramic factory where he slogged for 1200 rupees a month. Things did not come easy for him.

EARLY SIGNS OF PROMISE

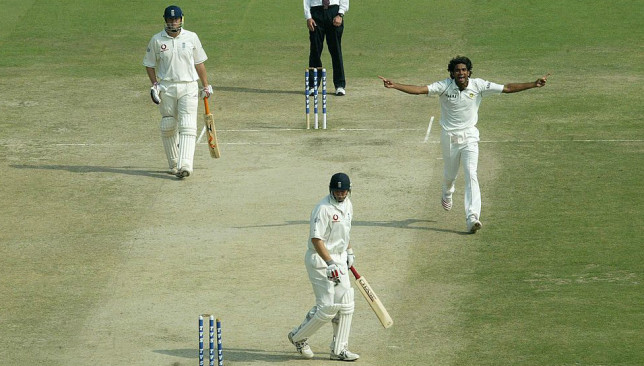

Munaf rattled the English in his debut series

The hype that preceded Munaf was nuclear. A one-time trainee at the MRF Pace Academy in Chennai, he was personally endorsed by Sachin Tendulkar to play his first-class cricket for Mumbai. Eventually, less than three years after he played his inaugural first class game, he received a call up to the national side, at that time hosting England in a Test and ODI series.

What made Munaf stand out from the crowd was pace. He was a genuinely quick bowler and, certainly in India, where excellent fast bowling is the exception rather than the rule, it was the biggest part of his mystique. Lightning speed is the one weapon in a bowler’s arsenal that captures the imagination like no other, and it seemed India’s answer to Brett Lee had arrived.

The first game for India augured well – it created a record. A performance of 7-97 against the English at Mohali – at the age of 22 – was the best ever by an Indian fast bowler on debut. His second Test, at his ‘home’ of Mumbai, was less successful – he collected only three wickets, but his economy was 2.85. Munaf had arrived.

He was a part of that class of young fast bowlers that broke into the Indian setup in the 2006-2008 period. Although he had been branded a fiery pacer to watch out for a few years before his debut, his rise in national colours was almost simultaneous with Shantakumaran Sreesanth, RP Singh and Ishant Sharma. They were Munaf’s classmates, in a sense.

They were an interesting bunch. The quartet had varying strengths, and they were supposed to be part of Mahendra Singh Dhoni’s revolution in Indian cricket. The pace spearheads of a new generation. No one who watched Ishant’s relentless harrying of Ricky Ponting on the 2007-08 tour to Australia would have doubted it.

Their weaknesses, however, were unfortunately coincidental, and a reason why they were found to be of highly limited utility once the initial excitement had faded – especially given that there were other, equally competent bowling alternatives that offered more upside.

LOSS OF MOMENTUM

Munaf soldiered on. A trip to the West Indies produced a 0-1 series victory, India’s first in the Caribbean since 1971, and 14 wickets at 33.07. Munaf’s early promise had been consolidated, and his repertoire was expanded to include more swing and varied length.

But this is where the early strides were halted. Munaf’s bowling action could be compared to Glenn McGrath’s, but that is where the comparison ended. The non-negotiables of fast bowling – the loss of accuracy, the heavy toll on the body – manifested in the form of recurring injuries and his ouster from the Indian side.

Appearances became sparse. His wickets-per-game in Test cricket fell from 4 to 1.57. He lost his pace dramatically, and instead directed his focus towards achieving more control and accuracy. They did not help him win his place back.

Munaf’s unhelpfully limited batting and fielding did him no favours either, especially when there is room for perhaps a single one-skilled player of his ilk – if that. It meant that if his bowling was not up to the mark, Munaf could not be depended on to produce an inspired piece of batting or fielding, and therefore the argument for his inclusion in a limited-overs game was significantly weakened.

This was something he shared with his aforementioned classmates, but he was undeniably a quality bowler in limited-overs cricket, offering at least one advantage or the other over his contemporaries in hard numbers. The facts are as follows: from 2006 to 2011, Munaf played 70 ODIs, conceding 2603 runs and collecting 86 wickets at an average of 30.26. His economy reads at 4.95, while his strike rate is 36.6.

In this same time period, Sreesanth, for example, has a worse economy rate (6.05), fewer wickets (62) and an inferior average (31.37). Ishant (5.73) also has a higher economy rate, as does Ashish Nehra (5.85). Munaf’s wickets-per-game in one-day cricket (1.22) in that time is better than Harbhajan Singh (1.04) and Praveen Kumar (1.16). He also boasts a better strike rate than either Harbhajan (49) or Praveen (40.4).

In fact, Munaf’s raw figures in this time are almost identical to those of Zaheer Khan. The left-arm seamer had an economy of 4.93, a strike rate of 36.4 and collected wickets at an average of 29.99, although Zaheer’s wickets-per-game read 1.404. It suggested Munaf was best used as a containing bowler, but was perhaps erroneously regarded as a spearhead wicket taker.

Munaf had serious anger issues towards the latter half of his career

Munaf’s appeal was further compromised by the mystifying need to play follower instead of leader, an oddly hamstrung instinct to be led rather than to lead. Now, the man who began as the answer to the country’s fast bowling woes was being talked of as the ideal third seamer, someone who played largely to fill up the overs and give the spearheads a rest.

However, it was a role he embraced to the fullest, and was a big reason why his place as India’s third most successful wicket taker in the victorious 2011 World Cup campaign (with 11 scalps) comes as a surprise to amny.

Weighing his numbers against contemporaries, the argument then changes to why he was not promoted as such a bowler from the off, given his talent for keeping batsmen on a reasonably short leash. Perhaps Indian cricket expected too much of him.

OUT IN THE COLD

Munaf began with awe inspiring aggression, his hair flapping maniacally about him. His hopes of an India recall have been long extinguished, but at 33, he still has a few more years left to tear it up on the domestic scene. Make no mistake about it, a recall to the side for him would be about as surprising as RP Singh’s ill-fated call up during the 2011 tour of England.

Munaf has not played for India in five years. It seems unlikely he will ever do so again, and an international career that promised excitement and amazement has ended with him out in the cold. But there is always the 2011 World Cup, and no one can erase Munaf’s triumph or his excellent performance from the pages of history.