While the world has changed how we meet and work, it hasn’t totally stopped us from getting on with our lives and seeking out new people, just in different ways, in or out of lockdown – mostly involving one type of technology or another.

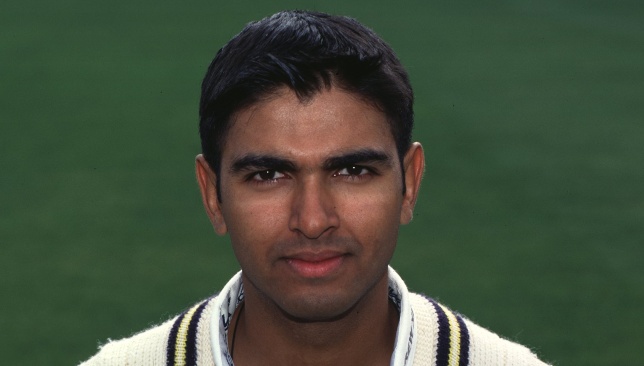

For myself one morning I interviewed over the internet Pakistan cricket’s chief executive: Wasim Khan is currently based in Lahore but with a heart and soul that is Brum. You can take the Brummie out of Birmingham but you can’t take Birmingham out of the Brummie and he is currently visiting in England alongside the Pakistan team who are also touring.

He was appointed chief executive in December 2018 and took up office the following February after working in a similar role for Leicestershire County Cricket Club.

As I fired up the meeting on Zoom, Wasim greeted me with a smile, asked how I was and with a cup of Pakistani chai in his hand, asked if it was okay if he kept on drinking it. I said he could bring in the corn flakes and it wouldn’t be an issue. Exchanging pleasantries, we both brought up football. I automatically assumed he was an Aston Villa fan but, no, he is die-hard City, growing up not too far from the ground. Birmingham City’s St Andrew’s stadium, that is, not Manchester City’s Etihad, for those who aren’t aware of any club outside the north-west.

I find Wasim to be a very likeable person, coming over as fair, honest and with plenty of integrity. We’re both first-generation British Pakistanis, children of the 1970s with similar likes and dislikes. No airs and graces about him whatsoever, just a nice lad from Birmingham, who is trying to change the world of Pakistan cricket.

With tea in hand, we moved onto the main points.

AM: You first took up cricket in school. Being from Birmingham, who or what was the main inspiration for taking up the game.

WK: My first experience of cricket was watching England play the West Indies in 1980. Prior to that I was really into my football, and used to spend most of my time playing that. And then playing cricket in the playground, and with friends on the street, by chance a teacher spotted me, and I guess that’s where my life changed. He took me for trials for Warwickshire under-13s. That’s where my journey started, but there were no other sources of inspiration. Just really by watching it on TV and being fascinated by this sport.

AM: Being the first British-born person of Pakistan-heritage to play county cricket, were there any obstacles in your path? Being Asian, it wouldn’t have been straightforward.

WK: I think the biggest obstacles at that time were the community. People were trying to fill my head by saying this isn’t for us, you won’t make it any further, why are you wasting time doing it? Also, at this particular point in time [1990], cricket wasn’t seen as a career.

Even when I became a pro-cricketer and had started playing, I still had a couple of uncles who said: “It’s all fun but when are you going to do a proper job?” because they never saw sport as a career. So all the stereotypical responses came back. I was lucky that I adapt very quickly to an environment, because I’d walked into an alien one, having spent all my life in inner-city Birmingham. Then all of a sudden at 13 it all changed. So when I became a pro-cricketer at 19, I’d had enough experience mixing with white people as I was travelling to matches, at under-13/under-16, and there were three or four of us Asian lads in the team. Though we learnt very quickly that you needed to adapt your style, at the same time you’re also educating yourself.

So when kids ask me now: “Is there any cricket club I can go to that isn’t racist?” I always point out: “Yes, every cricket club.” I say you might have the odd individual who may have some level of unconscious bias, but generally cricket clubs themselves don’t have issues, as all they see is someone with a bat or ball in their hand. Sport is a great way of bringing people together, so when I hear people saying that they didn’t get through because of racism, I say maybe it’s because you weren’t good enough. Just take responsibility and if you do that then you’ll be able to deal with more things in your life.

AM: With Warwickshire you played in the 1995 double-winning side with some of the greats of the game. How did this help in your own development?

WK: I did make my first-class debut in the double-winning year. In 1994 we had Brian Lara, in 1995 it was Allan Donald, and in 1996 Shaun Pollock. You’re in the dressing room with the likes of Gladstone Small, Neil Smith and Tim Munton, all seasoned pros, who’d all represented England; Keith Piper the wicket keeper who’d also been on England A tours. It was amazing. Firstly, it felt like a privilege to be sharing a dressing room with these guys, and secondly you didn’t want to leave that environment.

My debut was against Surrey. I didn’t know I was going to be playing until 10.15 on the day. I’d just made 150 in a 2nd’s game the day before, so went straight to the indoor school to train with the 2nd XI.

Due to an injury to Nick Knight, Asif Din came over to the indoor school, and said: “You’re playing, get your kit, come over to the changing room.” Literally no time for any nerves. Forty odd minutes later I was out there with the likes of Alec Stewart, Mark Butcher and Graham Thorpe.

AM: After moving on from playing, you were instrumental in running the “Chance to Shine” foundation, which has raised millions and has helped youngsters take up the game in state schools. What inspired you to do this? What was the motivation behind this project?

WK: After I finished playing cricket at the age of 30 at Derbyshire, where I had one season, like most cricketers you think what am I going to do for the rest of my life. I’d never been to university because every year for 10 years I went to Australia or New Zealand to play during the winters as a pro-cricketer, so I had nothing to fall back on. My only skills were cricket. So I started to go around to the local inner-city schools and did some coaching there. Then one day, literally out of the blue, I received a call from a lady who asked if I was Wasim Khan, I said yes. She then said she had Mervyn King, the governor of the Bank of England, on the line. I thought, “What on earth?” So he came on to the line and said: “Look, I’m a really big cricket fan, and I believe kids are being denied vital education opportunities in state schools by not playing competitive team sports,” – especially cricket, which was his love. The next day I was on a train to London and down to Threadneedle Street – as you do!

I turned up to be greeted by Mervyn King and Mark Nicholas, the former Hampshire skipper. They put their vision across to me on how they wanted to launch a campaign called A Chance to Shine, about getting cricket back into state schools, and how my name was constantly mentioned in this regard. I asked “Why me?” According to them, I was a graduate of the campaign before it ever launched, due to my own background.

They wanted to get competitive cricket back into state schools, raise £50m over the course of 10 years, to reach 2.5m children, wanting to reach to a third of state schools, which is approximately 7,000. This thought really appealed to me, because I got to play by chance rather than design.

Mervyn implied this wasn’t about finding the next England cricketer, more about changing lives through cricket, so they can learn about all the things that cricket gives you. He asked me to come up with a plan within three months. I started as the operations director, without really having a clue, self-taught myself in all the aspects of this business, and when I left nine years later, we had raised over £55m, which was outstanding. We’d reached 2.5m kids, of which a million were girls, across 39 counties. It was a fantastic scheme to be involved in.

AM: Chief executive of Leicestershire was your first senior post in county cricket. How much of an insight did this give you on the inner workings of cricket administration?

WK: I had kind of dealt with cricket clubs and cricket boards prior to joining Leicestershire because of my work with Chance to Shine, where we worked with various boards. So I had a good understanding of the process having been on both sides of the fence, having been a pro-cricketer. So there were no surprises. Don’t get me wrong, county cricket is really tough. You’re walking into a non-Test match ground that made a million pounds worth of losses in the previous four years prior to me going in and hadn’t won in red ball cricket for two years. That was the reality.

So, it was really hard to make inroads into that. You don’t have Test matches, any international fixtures. So we became a concert venue, hosted a women’s world cup, a whole host of things as a cricket club. In the first three years, we made a net profit after a number of years of making losses as a club. But it was great to be back and involved in the professional game once again, and I’m hugely thankful to Leicestershire in giving me that opportunity.

AM: Your next role was CEO of the Pakistan Cricket Board. What were the factors that attracted you to the role?

WK: I’d always been a lifelong Pakistan supporter. I was at Lord’s for the 2009 World Cup. Again with my friends at the Champions Trophy final in 2017. In 1982 I watched Imran Khan when Pakistan played against England at Edgbaston. You know I would have failed the Tebbit test had anyone asked the actual question.

For me [the Pakistan job] was a no-brainer. I was in the running for the Andrew Strauss job as director of cricket for England, in which I was one of the last two candidates, the other being [one-time Warwickshire team mate] Ashley Giles.

I had my interview, but pulled out because the Pakistan job came up. I was first interviewed online by their committee. There were about 300 applicants. Then I got invited at the back end of November 2018 for a face-to-face interview. It was something that stirred my soul. When its deeply entrenched within you, the opportunity to contribute on a global level and try and get Pakistan cricket up again, it was too good an opportunity and something I felt was in my DNA.

AM: In your role at the PCB, what have been the largest hurdles, especially in cutting down the existing number of first-class teams to six. What are the long term aims for this restructuring?

WK: One of the blunt statistics is that we were sitting in 7th in the Test match rankings, 6th in the ODI rankings. So when people were saying to me that our first-class system was working, my argument would be that if it was working, we’d be closing the gap between international and domestic cricket, which should mean we are performing consistently in red and white ball cricket in world cricket. Sitting 6th and 7th told me that the system wasn’t working. Don’t get me wrong departmental cricket (Pakistan cricket was made up of Bank and corporation teams. Habib Bank, PIA etc) had worked successfully once upon a time, but it was a tired system that needed to be changed.

The Prime Minister Imran Khan had a vision of six teams like the Australian state model, and that was something he articulated to the chairman and myself, that this is the route he wants us to go down. Our job was to then implement that, and it’s fair to say, as one would expect, a lot of politics was involved in trying to implement that. We managed to do it in eight months. The feedback from players who played in the first season has been superb. It’s created greater competition; we are improving the wickets; we’re using the Kookaburra balls which are used at international level. So there are a number of positive changes we’ve bought in. Ultimately, I keep on saying it’s not going to be an overnight success. You don’t change a culture that’s been built up over 40 years in six months. People need to show patience. The system will work, and we will start to see the dividends at international level.

AM: Quite a few cricketers lost their jobs due to this. Are there any schemes to help them in the short or long term?

WK: One of the things we have is that there are six cricket associations, in which the 1st and 2nd XI are on playing contracts: 192 players, roughly around 32 players per association, they all have domestic contracts. Below that we have 90 cities, who all feed into the six associations. For example, if there are a certain number of cities around Central Punjab, they will all make up the city associations. Below that we have club cricket. We have encouraged, and still do, all the coaches and players to try and get some formal coaching accreditation so they can deliver back, because 90 cities will require coaches. They’ll require umpires, officials.

There are a number of ways in which they can stay involved in the game. In my view, the biggest challenge we had was that everybody kept on saying we need to do something for the fact that we sit so low in international cricket. Then when you do something, they flip it on you, the argument being so many people have lost their jobs. My counter-argument is we keep it as it is and keep mediocrity going, or we revamp, we completely restructure, tear everything up, because it isn’t working, which means there will be casualties for some who were fringe players. You still had 38- and 39-year-olds playing first-class cricket. My argument is, how are they taking Pakistan cricket forward?

The media would argue they have families and this was their livelihood. I totally understand. I wasn’t exactly born with a silver spoon in my mouth. I came from inner-city Birmingham, so I know the difficulties in trying to earn money and a living for your family. Unfortunately, we’re not an employment bureau. Eighteen months ago, me and the chairman inherited an organisation with 750 people on the payroll. You look at that and you think how did we get to that situation? No one is asking questions of the previous regime. We’re the only country where everything was centralised; running nine international stadiums, we were paying all the costs for them, from the cleaners all the way up to the coaches.

So, in the six associations, we now decentralise everything and empower them with committees who run their own set-ups. And we find sponsors where we cover 50 per cent of the costs, in turn making them autonomous to run their own business. All with their own respective infrastructures. And we’re a long way towards that.

AM: What are the cultural and organisational differences you’ve observed in switching from Leicestershire to the PCB?

WK: From the culture that I’ve come from, I keep getting told by a minority of media that I have little understanding of Pakistani culture and cricket, which is slightly disappointing because I would hope I haven’t gone in with any arrogance or egotistical view of what I expected it to be. I’ve observed, learned and watched and I know what goes on. What I found there were certain individuals who worked within cricket, who had no interest in taking Pakistan cricket forward; they saw it as a job and their sole purpose was to secure their positions for the next 20 years. So, my view was that you’re working for a cricket board, Pakistan is in the doldrums, and we haven’t got the right people here, who haven’t got the energy, motivation or the hunger, or want to buy into what we’re trying to achieve. You have to have the courage to make the tough calls – which I have done.

So, I think the biggest challenge I found was some internal resistance to change, with attempt to stopping change from happening in certain areas. My view was that we had to motor on, my biggest strength being that I get things done. When I had my first press conference in February 2019, I was asked what were the key objectives on my agenda. I said firstly was to get international cricket back, secondly was to get the whole of the Pakistan Super League [T20 tournament] back in Pakistan, and thirdly to restructure domestic cricket. These were the things on my to-do list, which we needed to implement within 12 months. We have delivered on that.

AM: Some in Pakistan cricket circles still consider you to be an “outsider”. Does this bother you in the slightest? The sweeping changes you have made in both the domestic and international set-up are pretty brave and ground-breaking.

How confident are you this overhaul will pay off in the long run when there are people who are just waiting for you to slip up and fail?

WK: Starting with the end bit of your question – oh absolutely, without a doubt. I mean we’ve had a few bad days at the Test in the last couple of days, and already it’s due to the management. Even though I don’t walk out with a cricket bat or ball in my hand, I think we lose a sense of perspective. If you look around the world, CEOs don’t get blamed for things outside of their control. I understand that there is a disproportionate backlash when we don’t win and I’m prepared for that.

When individuals move to Pakistan to support the country, it’s disappointing that they are viewed in a certain way by agenda-led individuals. I have been highlighted as a British Pakistani, in a negative context, which shouldn’t be the case. British Pakistanis have a lot of love for their country, and see themselves as being Pakistani, so as in my case, to be called an “import” recently by one so called journalist was sad. The backlash that it received on social media upset a lot of people. When you look at the changes we have made, there is nothing that contravenes or contradicts the Pakistani culture. We are a cricket board, not an employment bureau. We’re there to make changes for the good of Pakistan cricket. You’ve got to trust the decisions and changes and see them come to fruition and be a success. You need to judge what success looks like. All you can do is focus on the processes you put in place, the changes you make. I can implement the business plans from commercial to structural and provide as much support to the cricketing side as possible in order to improve their running. I have no say in the coaching nor do I go into the nets with the players. Those things I don’t have any control over.

We have set up a high-performance system. We wrapped up the old National Cricket Academy, which to be honest with you wasn’t doing a great deal. It will claim: “We bought so-and-so players up.” It became a system that all it ran were camps, 10-15 camps per year with some of our players. Nothing was actually developed by design; it was by chance. So you find a good player like Naseem Shah or Shaheen Afridi at a certain age, you bring them into the system, and you coach them. We had no talent scouts, no coach education. We were the only country in the world where you could potentially do Level 4 qualifications in two months; everywhere else in the world it takes up to 18 months or longer. How is that beneficial to the players, being coached by someone who has gotten a certificate in only a matter of weeks?

There are a number of things we looked to change. We’ve got a system with the likes of Saqlain Mushtaq, Mushtaq Ahmed involved, both of whom have been in the English system. We have Nadeem Khan, who is a very good operator. We’ve bought in Mohammed Yousuf as the full-time batting coach at the High-Performance Centre in Lahore. Younis Khan is involved in the team. So there are a number of things which we are looking at, and which we’ve changed to bring in the very best of our ex-players, not because we’re doing them a favour, no. It’s that we know that they will add value, and they’re going to bring something to Pakistan cricket.

AM: International cricket has started returning to Pakistan in a big way with the PSL and the recent Sri Lanka and Bangladesh series. Getting the big teams like England and Australia to visit still remains a hurdle?

WK: This is the million-dollar question that I get asked all the time. One of the big goals was to get an MCC team over, or a non-south-Asian team, which we did in February this year, and that was a huge step, when we had the MCC team tour Pakistan. We had a lot of white first-class players who came, and who went back with a different reality, as they had come in with a totally different perception of what to expect. Similar thing with the PSL players. We had 35 international players, and I always maintained we as cricket administrators will always say if it is safe and that you should come. And you actually have word of mouth from the likes of Alex Hales, Dale Steyn or Shane Watson; the last was even quoted as saying that it’s the safest place to go and play cricket. There are bad people everywhere, yet the margin for error and tolerance level always seemed to be a lot lower for any incidents in Pakistan which is extremely unfair on us, basically due to the perception built up.

We have South Africa, England, Australia and New Zealand to tour within the next two years. SA are due in January, and we are hoping the pandemic dies down by then. I would love for England to come on a shorter tour. These are conversations that are to be had over the next few months. The question is why wouldn’t they come? We’ve evidenced our safety and security; the plans have been implemented year after year very successfully.

We would never get complacent as we know we’re only one bad incident away for people’s perception to change. But the government have done a phenomenal amount of work in cleaning things up in Pakistan. We’re confident now we can host sides and that it will happen. There is no reason as to why they shouldn’t come.

AM: In recent years the BCCI, ECB and Cricket Australia have emerged as the power group in international cricket. Most major ICC tournaments are being spread across these three countries in the coming years. Do you think this imbalance is good for international cricket and for other boards like the PCB in particular?

WK: It’s really interesting how this pandemic has highlighted the difficulties most face. Cricket as a game will need to recalibrate and look at its financial structure. You have cricket boards who are now financially struggling, so if you lose hosting a series against Australia like one of the sides did, it’s imperative that you play that at some stage as it generates so much broadcasting revenue for them. Most cricket boards are reliant on ICC handouts and broadcasting revenue, while those big three aren’t, so therefore the whole financial distribution model needs to be looked at.

If you get England Australia, and India playing each other all the time – because that’s where the money is – it’s going to become a very boring sport. The beauty of the game is the diversity of all teams playing against each other. We’re extremely fortunate, we have done a lot of contingency work to see what the next three years look like for us. We’re in a decent position financially. Nevertheless we are reliant on ICC funding. We need to address that as a global sport and now is the best time to look at the redistribution model, to make it fairer to smaller countries. The game will suffer if this is not addressed now, so something like this doesn’t happen again.

AM: Where would you like to see Pakistan cricket, domestic and international, in terms of development over the next two years?

WK: Our standing. I’d like us for us to be in the top three in Test and ODI formats. Is it a realistic aspiration? Absolutely! In T20 we want to reclaim that No 1 position, which can be achieved, especially with two men’s T20 World Cups in 2021 and 2022. Winning a cup is a major goal for us.

The high-performance system running, the cricket associations running, having proper cricket in clubs and schools through the associations.

We have now developed a delivery framework. A gentleman called David Parsons, who has worked in high performance for the ECB for 11 years and helped them get to No 1, has done a huge assessment piece on Pakistan over the last six months, so now we’ve put something together – what is called the Pakistan way. It’s not about imposing the English system. Along the way getting valuable input from the likes of the Wasim Akram’s, Rashid Latif’s and the Misbah-ul-Haq’s on what success looks like, on how we want our teams to be playing moving forward, from Under-19s to women’s cricket.

Youngsters coming in by design from under-13 upwards, based on merit rather than some kids’ rich parents shoving a few rupees into the hands of a coach, who then move them up the system. We want the very best players from under-13 upwards from across the six associations.

Off the field for the first time we have put together a five-year strategic plan, which is to provide Pakistan cricket with a viable direction over the next five years. A big element of that is based on our commercial strategy. Previously the PCB have not had relevant marketing teams, now we have put in place a commercial strategy team. We have valued everything from ground naming rights to shirt sponsorship to cricket association sponsorships that the team are out there selling. My vision is that the percentage of income we receive from the ICC as a percentage of overall income we generate on an annual basis is vastly reduced, so we can become more sustainable.

Moving forward, employing hungry and motivated people, who want to make a change and see a difference, and ultimately care about moving Pakistan cricket forward. I am, and will give it my best shot.

AM: Finally what do you do when not working? How do you relax in this environment?

WK: Mostly time with my blessed and amazing family. Luckily I’m a gym person, and there’s one in my apartment building – by the way, for which I personally pay the rent. I do a lot of driving, which I enjoy, and it comes with the job. Netflix is a must. Being a new environment, it’s difficult just because of the nature of the place. People know who you are, you get plastered all over television, people want to ask you all sorts of questions. I like going out but have to be on my guard at times, because there are certain conversations people might want to have.

I definitely stay away from Pakistan cricket talk shows as I find that apart from possibly one, there is limited value through its discussions and debates. When you concentrate on characters and people and not enough time on policies, procedures and performances, then you add very little.

Lastly, I want to say thank you to all the people who have come out and supported me. The negative media scrutiny made it challenging. But I want to say thank you to the Pakistani people and fans from all over the world, especially fellow British Pakistanis, who have wholeheartedly supported me throughout with messages of support. People have seen the changes and when you do a comparative study of what PCB has done as an institution in the in the previous 5 years and what we have achieved in the last 18 months, the evidence speaks for itself.